Securing Life's Essentials: Building a plan for targeted bill support in regulated markets

Ar y dudalen hon

Executive Summary

The cost-of-living crisis has been an incredibly difficult time for millions of households, with many seeing their budgets stretched to breaking point and beyond. At Citizens Advice, we’ve seen a huge shift in the number of people needing crisis support and coming to us with budgets which even our expert advisers can’t balance. This crisis exposed the patchwork nature of support, available both through the welfare system and also through bills support schemes aimed at helping those on the lowest incomes access essential services.

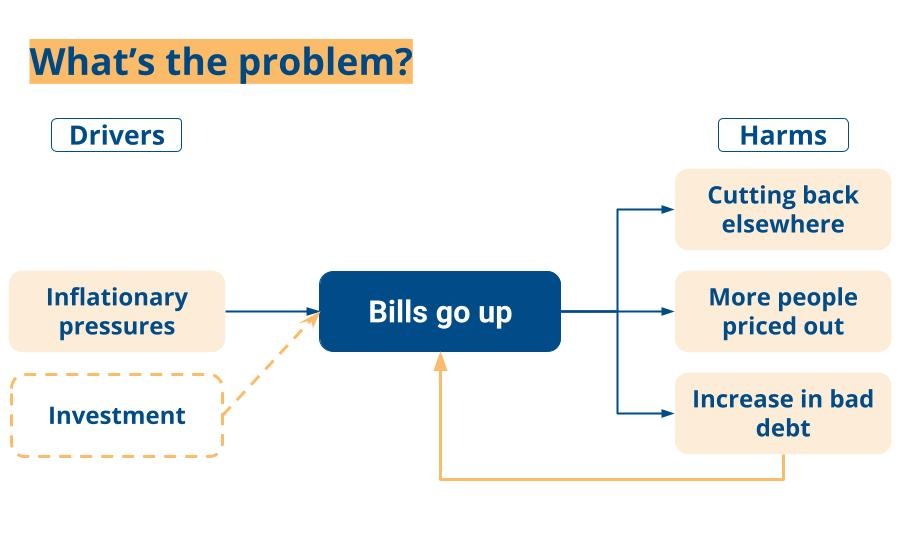

Inflation has fallen since its double-digit peaks - but household budgets remain on a knife edge. Half of households in Great Britain cut back on two or more essential services in the past year[1] - and over 1 in 7 cut back on at least one essential to the point where it impacted their daily lives.[2] This impact falls disproportionately on households with the lowest incomes.

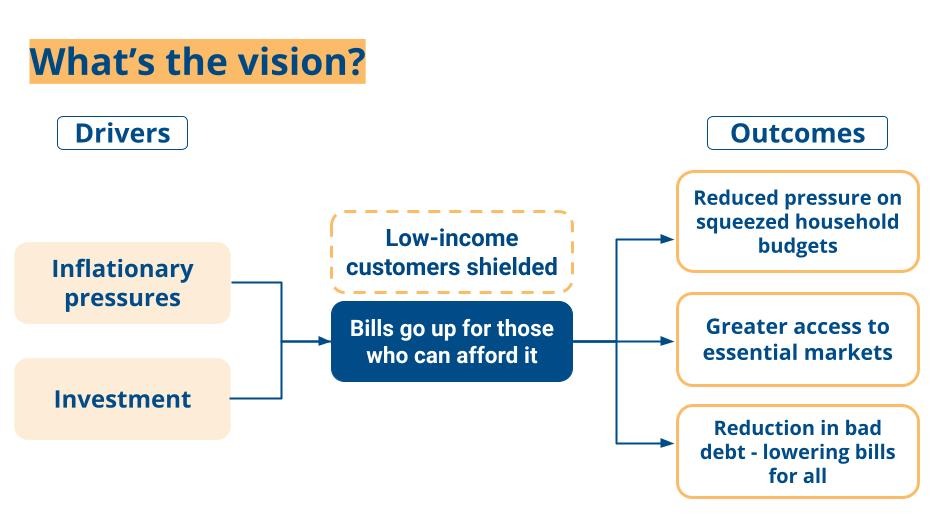

This lack of financial resilience is bad for families, making it harder for households to absorb unexpected shocks. It’s also bad for businesses as it leads to higher levels of debt needing to be written off. This all comes at a time when we know huge levels of investment are needed across markets to transition to Net Zero, improve our water and sewerage systems, and expand internet connectivity. This will all put further pressure on bills at a time when many can least afford it - unless there are mechanisms in place to shield those on the lowest incomes.

This report sets out these challenges - and how we can navigate our way to a solution. Our focus is on the role that targeted bill support - also known as social tariffs - can play in providing a buffer for households on the lowest incomes. This would ensure that they can access essential services at an affordable price and protect them from both predictable price rises and those, like we have seen in recent years, which are less predictable. The report looks at the current patchwork of support which exists across four markets: energy, water, broadband and motor insurance. These services are essential for day-to-day life, but we've seen more and more people struggling to access them without making sacrifices. We've found that targeted bill support isn't working as effectively as it should be:

Energy support needs to be more generous and better targeted to address the historically high energy bills which households continue to face.

Water social tariffs, which are set by individual companies, vary significantly both in terms of who is eligible and what they receive - leading to an unfair postcode lottery.

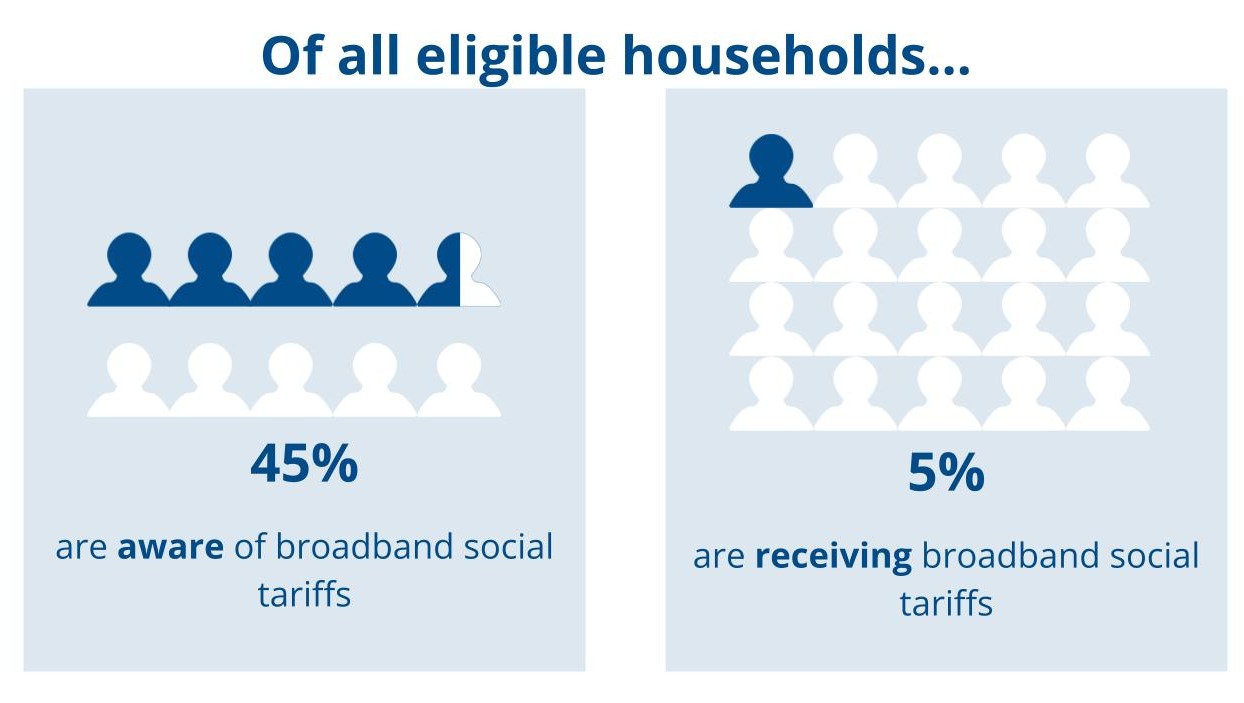

Broadband social tariffs suffer from persistently low levels of uptake, with only 5% of eligible households signed up.

Motor insurance lacks any form of bill support scheme.

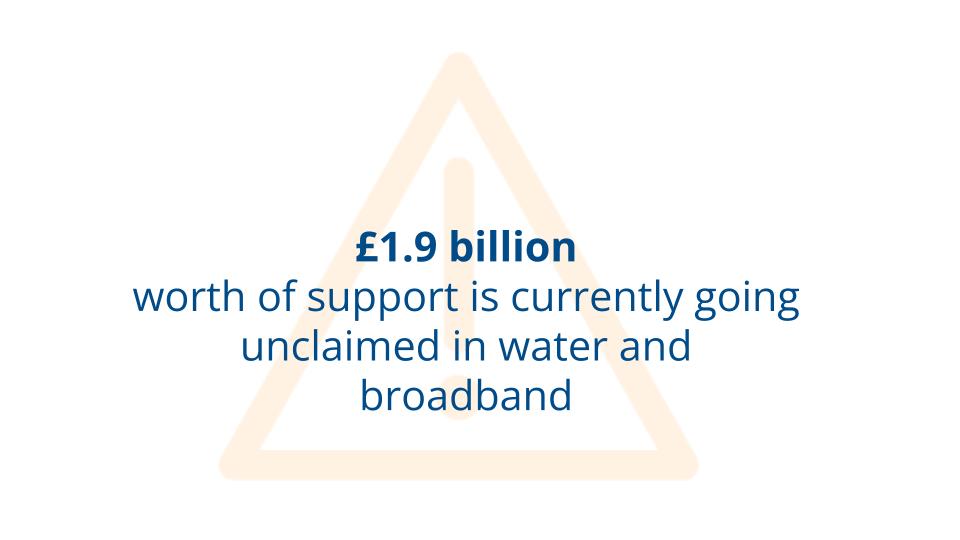

These are problems worth solving. We estimate that £1.9billion of support goes unclaimed in water and broadband alone.[3] As we set out in the report, these schemes have developed independently of each other - and there's a lack of strategic thinking about how they fit together. This means that good practices set up in some sectors - such as the automation of the Warm Home Discount in England and Wales - haven’t been applied to other sectors. This has also led to a complex landscape of support where it's difficult for consumers to understand what they're eligible for and how to access it.

This report is the start of a collaborative project between Citizens Advice, the Institute for Public Policy Research and Policy in Practice, funded by abrdn Financial Fairness Trust. The project aims to set out the need for social tariffs, the problems with current schemes, how bill support schemes can be better designed and, critically, how any scheme can be practically implemented across the four key markets we're focusing on. We set out in the final section of the report some guiding principles:

While the focus of this project is on establishing a coherent and effective system of social tariffs across key essential markets, there's also a pressing need to see improvements quickly to the support currently on offer. Given the urgent need for the government to take steps to address living standards, we also set out some recommendations for actions which the government can take now to improve the support currently on offer.

Our recommendations for actions the government can take now to improve the support currently on offer:

Expand the Warm Home Discount and move from a flat discount to a tiered discount depending on the needs of different households.

Water and broadband providers must do more to proactively contact customers to offer them a social tariff, aided by proactive data sharing from DWP to utility companies to ensure suppliers know who to contact.

Start the process of ending postcode lotteries in broadband and water support by using existing powers available to Defra and DSIT:

Water - Defra has powers under the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 to set guidance for suppliers on how their social tariffs should work. As an essential first step towards standardisation, this power should be used to set out a single approach to eligibility.

Broadband - the Communication Act 2003 gives DSIT the power to direct Ofcom to report on how a mandatory social tariff, common across all providers, should be structured and funded. This should be triggered immediately.

1. The challenge we face

1.1 High essential bills have driven many households to the brink

The cost-of-living crisis has laid bare the increasing challenge low-income households face in affording their essential bills. High inflation and sudden price shocks have driven up the cost of utilities and basic services, stretching many household budgets beyond their limits. Since the start of 2024, over half of the people we’ve helped with debt advice at our local Citizens Advice offices have been in a negative budget[4] - which means they can’t cover their essential costs, even after expert help to bring bills down and maximise income. And we’ve estimated that 5 million people nationwide are in the same position.[5]

I'm depressed because literally, I'm lucky if I have anything left.... when I get my income... It comes in approximately half past midnight. And by six o'clock that same day, six o'clock in the evening, so just over 18 hours later, I'm broke again...

When your income can’t stretch to cover all of your day-to-day needs, you’ve only got a few options: fall behind on bills, borrow to cover your essential costs, or cut back on life’s essentials. And despite a perception that the cost-of-living crisis is largely behind us, worrying numbers of people are still having to take drastic steps in the face of unmanageable essential costs.

When it comes to the essentials - in this case energy, water, broadband and car insurance - in the past year half of British adults cut back their spending on two or more of these bills.

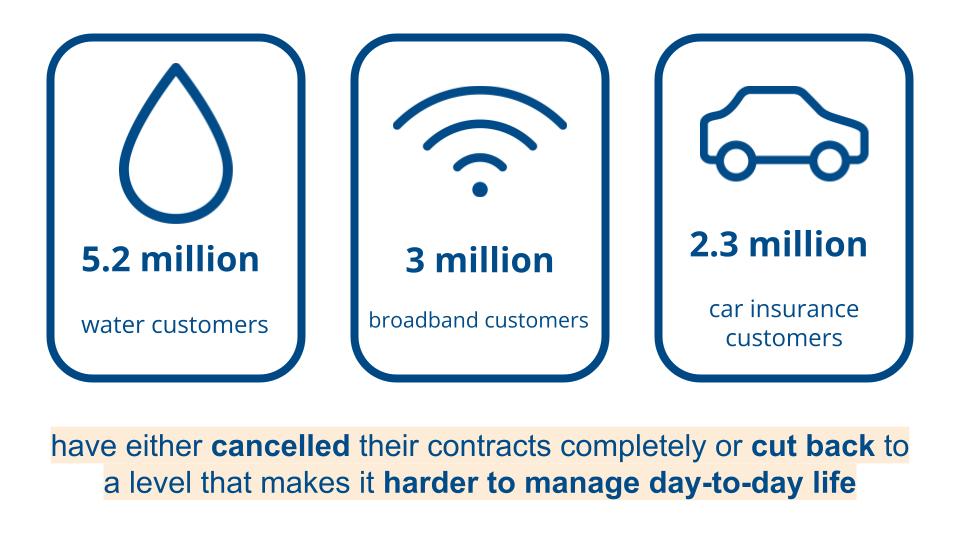

For some, this has been more detrimental than others. Millions have been pushed to the edge trying to pay these essentials - or have cancelled altogether.[7]

12% of pre-payment meter customers have been temporarily disconnected in the past year.

Overall, just over 1 in 7 people have stopped spending or cut back to a level that has had a detrimental impact on their lives in at least one of these bills.

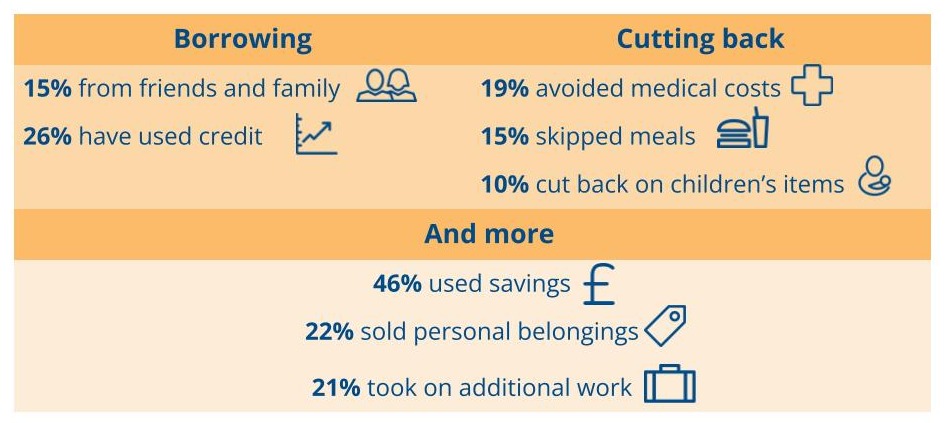

In the past year, in order to afford the essentials, people have been:

Significant numbers are falling behind on essential bills too. Nearly 8 million people have fallen behind on one of their energy, water, broadband or car insurance bills in the past 12 months.

The challenge is greatest for those on low incomes. Modelling by the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) estimates that those in the poorest decile are currently spending 21% of their disposable income on energy, water, broadband and car insurance costs alone. By comparison, households in the fifth decile spend an average of around 10% of their disposable income on these same bills - and for those in the 10th decile, it’s around 5%.

This is a big shift. IPPR modelling finds that 2.8 million households are estimated to be spending a fifth or more of their disposable income on these utilities - an increase of around 1 million households since 2021/22.[8]

1.2 The challenge of high bills isn't going away

Across markets, bills are set to keep rising. Huge levels of investments are needed across the board - to transition to Net Zero, improve our water and sewerage systems, and expand internet connectivity. This will continue to put pressure on household budgets.

Utility bills are expected to rise significantly over the coming years. The energy price cap will rise by 10% this winter, which could force 6.9 million households to turn off their heating and hot water[9] - and wholesale prices are likely to remain higher than pre-crisis level for the rest of the decade. In addition, the transition to net zero may require steps that could also push up bills for some consumers, adding further pressure.

This Cost of Living crisis has literally put me into debt, like you wouldn't believe. I have never been in debt with my gas and electric [until now]. Never.

Ofwat’s draft determinations for PR24 to allow for average water bills to rise by £94 per year over the next five years - a 21% increase on current bills.[10] Within this average, some bills are slated to rise by significantly higher amounts: for Welsh Water the proposed increase over the five years is £137, while for Southern Water it’s nearly double the average at £183. IPPR estimates that these rises could push the number of households living in water poverty - defined as spending 3% or more of disposable income on water - from an estimated 2.7 million today to 3.4 million by 2029/30.[11]

In the broadband market, consumers have seen hefty in-contract price rises applied to their bills over the past few years, driven by contract terms linked to inflation. Some consumers’ bills will have seen cumulative increases of 38% over the course of above-inflation price rises in 2022, 2023 and again this year.[12] At the same time, we estimate that 1 million people cancelled broadband contracts in 2022 due to not being able to afford it - with people on Universal Credit 6 times more likely to have been priced out.[13] Despite Ofcom introducing a ban on price rise terms explicitly pegged to inflation, providers are still free to hike bills mid-contract - so there’s no reason to expect that prices won’t continue to rise above inflation in the future.

In the car insurance market, steep price increases over the past couple of years show no sign of abating or returning to where they were previously. Premium prices across 2023 were up by 25% compared to 2022 - and premiums from the first quarter of this year were up by a further third compared to the same period in 2023. In cash terms, this means that the average person will have to find an additional £157 to retain their car insurance in 2024 compared to last year.[14] This figure will be larger still for people on lower incomes, who pay significantly more for their car insurance on average, thanks to a combination of postcode pricing and extra charges for paying monthly.[15] We estimate that more than 1 million people had to cancel their car insurance in 2022 alone due to pressure from rising bills - before the worst of these recent price rises had kicked in.[16] The Association of British Insurers has cited inflationary pressures driven by high energy costs and problems with supply chains as a key reason for the spike in car insurance costs over the past couple of years.[17] If such market volatility persists, car insurance prices may continue to increase with nothing in place to ensure affordable access for low-income drivers.

1.3 Affordability challenges are bad for business too

The negative effects of these essential bills being unaffordable for many aren’t only felt by struggling households. Failing to tackle affordability in these sectors also spells trouble for businesses, in two key ways.

Firstly, prices that are unaffordable for a significant number of consumers can lead to an accumulation of consumer debt. Consumers who fall into arrears because of being in a negative budget are unlikely to be able to repay their debts - and when consumers cannot repay these debts, these arrears become ‘bad debt’ for companies. Bad debt creates significant additional costs for firms, both in terms of managing these debts and, eventually, writing them off. This ultimately filters down to other consumers, who end up paying for these debts through their bills. The Consumer Council for Water has estimated that bad debt across the water sector adds roughly £13 per year to every customer’s bill.[18] In the energy sector, an estimated 5 million people across Great Britain are living in a household with energy debt.[19] Total energy debt for domestic consumers has now reached over £3 billion - and extra debt costs are adding £28 per year to the average energy bill.[20] Measures which help tackle affordability will also have the effect of reducing the number of people in debt, and prevent some of the accumulation of new bad debt. As a result, some of the cost of these measures would be recovered through a reduction of the cost of recovering and writing off that debt.

...at the moment I don’t see a way out of not having money troubles, it's always going to be a burden.

Secondly, as discussed earlier, there’s a need to invest significantly over the coming years across several of these sectors, to ensure upgrades to key infrastructure and core policy objectives are delivered: a transition to net zero, improvements to our water network and digital connectivity across the UK. This is likely to lead to higher bills for consumers. We’ve already seen broadband providers justify the significant in-contract price increases of the past couple of years as necessary to fund network infrastructure upgrades.[21] And water companies have repeatedly stressed that the significant increases to bills requested as part of Ofwat’s price review for the next 5 years are needed in order to support investment in infrastructure to tackle sewage spills and water security issues.[22]

Certainly, there are important questions that should be asked about who should foot the bill for this investment. But assuming that at least some of the burden will fall on consumers, there will be further upward pressure on bills - which will likely mean more people who can’t afford their bills, and more bad debt in turn. Not only does this increase the risk of consumer harm - it also presents a political risk that support for necessary investment is undermined by the negative impact on low-income consumers.

I got sent a bill that was just ridiculously inflated to the prior month, and again, rather than querying it, I didn't pay it, and then the following month came through and it was a similar rate and I've just let it build up...

1.4 We need to be looking at all options in the toolbox to solve the cost-of-living equation

Ideally everyone should have enough disposable income to cover all their essentials - and so arguably the problem of affordability is one of inadequate incomes, which should be addressed through a combination of wages and benefits. In practice, however, targeted measures to reduce the cost of essentials have a critical role to play in solving the cost-of-living equation for those on low incomes.

This is particularly clear given the tight fiscal rules of the current government. It's implausible to imagine tackling the full extent of cost-of-living issues via income-based levers alone, given the scale of public spending increase that would be required.

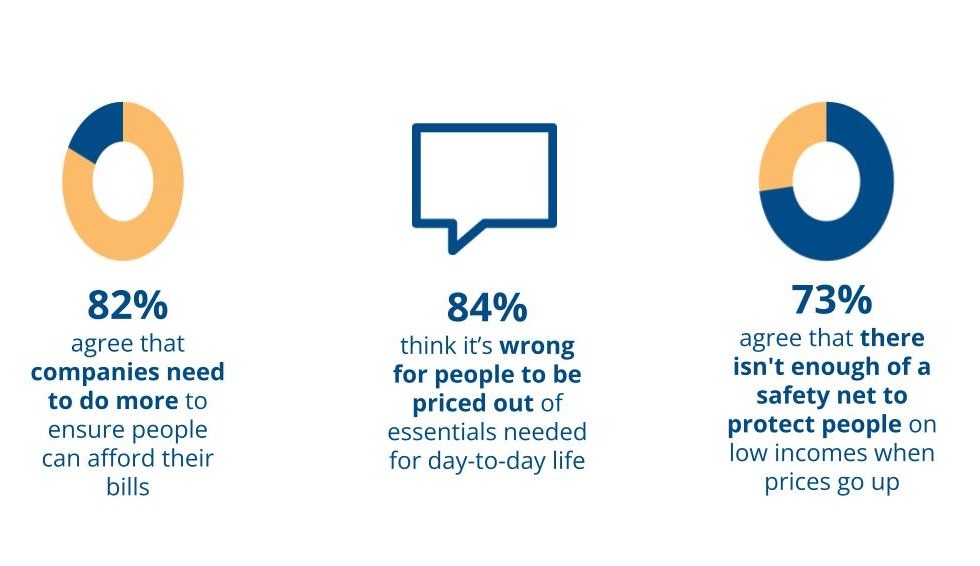

There’s broad public support for asking companies to play their part in making sure people can afford their services:

‘Social tariffs,’ or targeted bill support schemes for essential services - which give reduced rates or discounts for low-income or vulnerable consumers - are the most plausible and practical lever for the government to pull on the expenditure side of the cost-of-living equation. By providing targeted support with essential bills, social tariffs mechanically increase disposable income for those eligible. But they also act as a safety net to keep people connected to life’s essentials, shielding them from the worst effects of price rises and helping to ensure that household budgets are sustainable. In concrete terms, this makes it less likely that people end up cut off from the energy they need to heat their home; the internet or insurance they need to look for work; or in debt for water they need to keep clean.

Social tariffs are not a new idea, but existing schemes are falling short of the mark in several respects.

2. Existing bill support schemes are falling short

Targeted bill support schemes of some kind currently exist in the energy, water and broadband markets. But these schemes have many problems, including:

postcode lotteries which can mean identical households can receive completely different levels of support simply because of where they live

poor levels of uptake which is leaving an estimated £1.9 billion of support unclaimed

poor targeting of sometimes insufficient support which can mean even where people are receiving support it isn’t enough.

As a result they're underperforming - both in terms of delivering meaningful cost-of-living support to low-income households and in terms of acting as safety nets to keep people connected to essential services.

2.1 The state of support in energy, water, broadband and motor insurance

In this section we look at what support is on offer in each of the four markets and highlight why current mechanisms aren't meeting the challenges consumers are facing.

What schemes exist?

Both the Winter Fuel Payment (WFP) and the Warm Home Discount (WHD) are statutory schemes to support those struggling with energy costs. The WFP, a government-funded scheme, gives £200-£300 towards energy costs to certain older people (previously it was given to all energy consumers over a certain age, but the Government recently restricted the scheme to those in receipt of Pension Credit and some other means tested benefits). The WHD, which is funded by a levy on consumer bills, gives a £150 one off payment towards energy bills to around 3 million households who either receive the Guarantee Element of Pension Credit or receive means-tested benefits and live in a home with a high energy cost score. Most of this support is delivered automatically.

What are the issues?

The level of support delivered through the WFP and WHD schemes is inadequate to the scale of need amongst energy consumers. As we’ve previously outlined, the level of discount offered through the WFP has not kept pace with inflation. The level of support offered through the WHD, meanwhile, has never been set according to an assessment of need - and the amount delivered has fallen behind both energy costs and wider inflation. And the eligibility criteria mean that households with low and medium energy usage get no support, even if their financial circumstances mean they really struggle to cover their bills.[23]

What schemes exist?

All water companies offer some kind of bill reduction scheme for consumers struggling with their water bill. Each company has its own set of eligibility criteria and form of discount - some companies cap bills at a certain level, while others offer percentage discounts. These schemes are funded via cross-subsidy between consumers in each company’s customer base - and the level of cross-subsidy has to be set by ‘Willingness to Pay’ research conducted by water companies with their customers. The average saving across all of these schemes is £150 per year.[24] In addition to company-specific schemes, there's the national WaterSure scheme (WaterSure Wales in Wales). This caps bills at the average bill price of households in receipt of means-tested benefits who have high essential use of water in the area.

What are the issues?

The differing eligibility criteria and generosity levels of company-specific schemes create a significant postcode lottery in water bill support. Discounts vary from between 15% and 80% - and annual caps vary from just under £80 to over £360. This leads to a situation where households with identical finances, in close proximity to each other, will have access to a totally different level of support (or none at all). For example, a household in Basingstoke with a yearly income of £18,725 and not in receipt of benefits will qualify for social tariff support from their water company South East Water, meaning their bills will be capped at £146.94 per year. Meanwhile, a household with an identical income and circumstances living only 15 miles or so away in Reading would qualify for no support with their bill from their provider Thames Water.[25] Unlike energy support, which is applied automatically to eligible households, in the water sector customers have to apply for support, often with complex applications that require evidence of household income. This leads to lower levels of uptake, meaning that a significant amount of the support available through these schemes isn’t currently delivered. According to the Consumer Council for Water, water suppliers have earmarked around £500 million in total for their social tariff schemes - yet in 2023-24 only £260 million in social tariff support was delivered.[26]

What schemes exist?

For broadband, social tariff schemes take the form of lower-price broadband packages available to those on low incomes, typically defined by being in receipt of Universal Credit or other means-tested benefits. The majority of broadband providers offer some kind of social tariff package. As with water, the specifics of the package - price, connection speed, additional bundling options - vary by provider. Social tariff packages save eligible consumers an average of £200 per year.[27]

What are the issues?

Uptake of broadband social tariff packages is extremely low. The latest Ofcom figures put the number of households currently in receipt of a broadband social tariff at 380,000.[28] According to Policy in Practice, given the estimated number of households in receipt of relevant means-tested benefits, this could equate to an uptake rate as low as 5%. They estimate that that would leave £1.68 billion in social tariff support unclaimed across the sector.[29] As with water, customers are expected to apply to their provider, rather than being offered the support proactively. Over half of eligible households are unaware of social tariffs according to Ofcom[30], despite a big push to publicise them during the pandemic when many households had to suddenly switch to working and learning from home. The fact that only around 1 in 10 of consumers aware of the scheme have signed up suggests that merely attempting to further raise awareness is unlikely to lead to significantly higher levels of uptake.

Beyond these existing schemes, there are essential services such as motor insurance where no targeted bill support is currently in place - despite premium price rises well above inflation in recent years making it extremely difficult for low-income households who rely on having a car to stay insured. In the 12 months to June of this year, the amount our debt clients were spending on car insurance rose by an average 23.5% - a sharper rise than any other expenditure category.[31] The total lack of safety net for people on low incomes facing such steep rises is leading to serious consequences for lots of people for whom having a car is essential to their employment, health or safety.

[32]

2.2 A lack of strategy creates a mess from the perspective of consumers

Zooming out from the particular issues with the specific schemes outlined above, what is apparent is that there is a lack of overarching strategy driving the design and delivery of targeted bill support across essential markets. The energy schemes are statutory, but those in the water and broadband markets are voluntary. Eligibility is fixed in energy, but left to firms in other sectors. Funding mechanisms allow for risk pooling between providers in some areas but not all. Within markets, the level of generosity can change from provider to provider. And there are some essential markets, like car insurance, where no targeted bill support currently exists - despite being a legal requirement for anyone who relies on a car, and many struggling to afford it.

This complex and patchy landscape of support has real consequences when viewed from the perspective of consumers. Those in urgent need of the support available across various social tariffs end up having to navigate different support schemes with little or no commonality between them. As Policy in Practice has noted, this creates barriers both to awareness and to successful application.[33] With different schemes in different markets, it’s less likely consumers will know about all of the possible sources of bill support available to them - and even where they do know, the need to navigate complex eligibility criteria, submit multiple applications and provide onerous evidence of eligibility can all prevent people from successfully accessing the support they’re entitled to.

The result is that existing bill support schemes are failing to provide the kind of robust safety net needed to keep low-income households reliably connected to the services essential for day-to-day life. And without strategic improvements to the design and delivery of these schemes, they’re not going to function effectively to shield struggling households from price rises in the coming years, or future price shocks.

3. Short-term improvements: unlocking existing support

The need to shore up household budgets is urgent. At Citizens Advice, we’re helping someone every 5 seconds with a cost-of-living issue. The Government needs to be looking at all available levers to put some money back into peoples’ pockets - and that should include tackling the high cost of essential bills for those least able to afford them.

Importantly, there are steps the Government can take in the short term to make concrete improvements to the support that’s currently available through existing social tariff schemes. This section sets out the three immediate steps that the government could take to start the process of fixing the problems we see with existing targetted bill support.

Targeting energy support to those who urgently need it this winter

We’ve recently outlined how reforms to the Warm Home Discount scheme could mitigate a lot of the harm currently facing struggling energy consumers this winter.[34] We’ve proposed that the WHD scheme should be expanded so that it reaches more households on eligible benefits, but also targeted (using the existing WHD mechanism) to provide a higher level of support to those with the highest energy needs. Households on eligible benefits with high energy costs would get a higher payment - with decreasing levels of support for those with lower energy needs. This would expand support and avoid steep cliff edges for households that fall into different thresholds. Our proposals could provide discounts of a third off a typical bill (~£580 from October) to low income households with the highest energy needs, with support tapering down for those with lower needs.

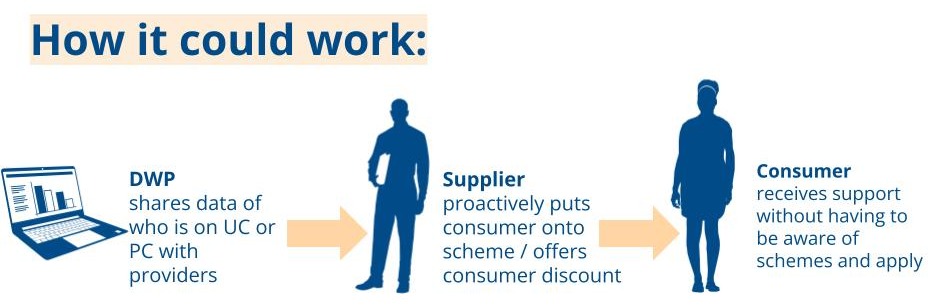

Driving uptake for water and broadband social tariffs with proactive data sharing

The Warm Home Discount scheme uses DWP data, in conjunction with data on how much energy people's homes are likely to use, to apply the vast majority of scheme awards automatically without the need for consumers to apply. But as things stand for water and broadband social tariffs, DWP data is only sometimes being used by providers - and only then to confirm (or partially confirm) eligibility once a customer has already applied for support.

An effective way of boosting uptake for water and broadband social tariffs would be for providers to proactively offer support to those on means-tested benefits as they would be, or are likely to be, eligible for social tariff schemes. To enable this, the DWP should proactively share data to utility providers to let them know which of their customers are on Universal Credit (UC) or Pension Credit (PC). We believe that the legal gateways for this data sharing already exist under the Digital Economy Act - but, if these are not sufficient, consent could be sought from UC and PC recipients as part of the application process.

Tackling postcode lotteries in available support

There are significant inequities in the overall level of support available to different households in the same financial situation across the country.

For water, there are large disparities in both eligibility and generosity between different company schemes. This not only creates a postcode lottery, but also means consumers often have to navigate complex application processes that require them to provide a lot of information. Standardising generosity in the long run requires a sustainable funding model for cross-market provision of support that targets need equally regardless of water supplier. But steps can be taken in the short-term to standardise eligibility around criteria that can be assessed via data available from DWP and data available to water suppliers regarding usage. This would go some way towards tackling the postcode lottery, and allow for more seamless use of DWP data sharing to drive uptake. Guidance to this effect can be issued under the Flood and Water Management Act 2010 to drive good practice across the sector.

For broadband, there is significant variance in the connection speed and price point of different social tariff schemes. Eligibility criteria, minimum connection speed and price of schemes should be standardised to remove these disparities. This can be achieved by triggering the provision in Communication Act 2003 s72D (as amended) that allows the Secretary of State to direct Ofcom to swiftly conduct a review of broadband affordability and make recommendations on introducing a mandatory, standardised social tariff.

Driving uptake of existing schemes via smarter use of data sharing will help to unlock the £1.9 billion that is currently going unclaimed. The average amount saved through access to a water and broadband social tariff scheme is £350/year per household. Taking steps to tackle unfair postcode lottery effects within these schemes, meanwhile, will mean that these unlocked dividends are available to those who need it most across the country, regardless of where they live.

4. A longer-term vision: a coherent, comprehensive suite of targeted bill support across essential services

If bill support schemes are to function in the longer run as an effective and efficient part of the broader safety net of support measures for low-income households, these shorter-term steps need to be underpinned by an overarching, cross-market strategy. This is essential from an operational perspective - to ensure that an adequate level of support is delivered across essential markets, appropriately targeted to those with the greatest need, but also to make effective and efficient use of administrative infrastructure. But it’s also essential from the perspective of consumers - if the barriers that prevent many from accessing the support currently available are to be overcome, all schemes need to be designed to minimise friction in the consumer journey.

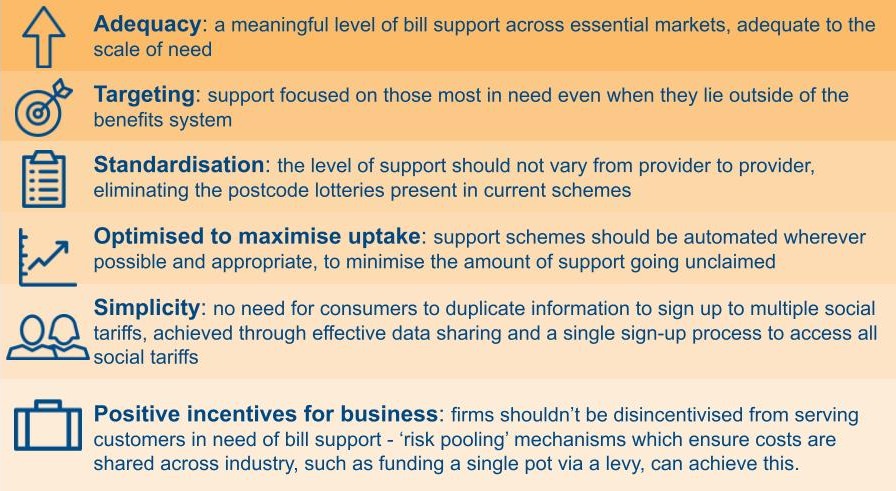

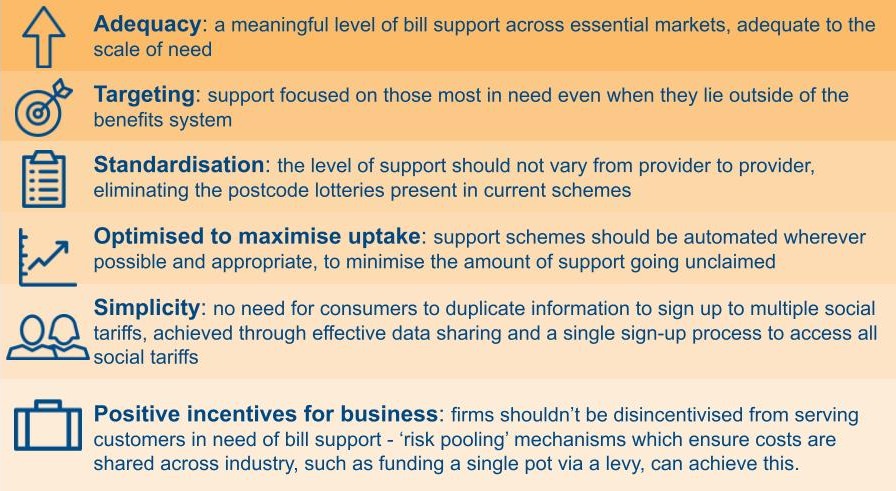

We think a strategy for building a longer-term, sustainable suite of bill support across essential markets should be guided by the following principles:

These principles are a starting point - but using them to flesh out a strategy for designing and delivering an effective suite of social tariffs will require work. This is particularly true where some of these principles might pull in a different direction to one another, requiring a consideration of potential trade-offs in policy design.

For example, there is a clear trade-off between adequacy and targeting - more specifically, the question of who should be eligible for support schemes, and of how much support these schemes should deliver. Roughly speaking, the broader eligibility for a social tariff scheme is set, the less generous a level of support it will be able to provide to those eligible - that is, without increasing the size of the funding pot required to fund the scheme. There are, of course, important questions about how social tariffs should be funded - whether by government, company profits, consumer cross-subsidies or some combination of the these - and what scope there might be to increase the overall amount of funding, and therefore the overall amount of bill support, available within each market. But expanded funding for social tariffs schemes wouldn’t in itself resolve the issue of whether it is better to offer a modest level of support to a larger number of people, or a significant level of support to fewer.

Targeting and simplicity also pull social tariff design in somewhat different directions. The more that support is targeted at narrower groups of consumers, the more data is likely to be needed to assess eligibility. But having more complex, multi-faceted eligibility criteria - especially if there are different targeting mechanisms operating in different markets - creates a more complicated and confusing system for consumers to navigate. Designing eligibility criteria to allow for automated eligibility and uptake would remove this burden on consumers - but it would also limit options for targeting to those that can be operationalized via available data sources.

Beyond these tensions, there are additional issues that arise when we start to think about a more coherent suite of social tariffs. Chief among them is the issue of cliff-edge effects. One effect of designing bill support schemes to maximise uptake across multiple markets is that it will create a more significant drop-off in support when a household moves just outside of the eligible group. This is especially true if eligibility across markets is standardised according to criteria that can be automated - for example, being in receipt of means-tested benefits. As with other sources of targeted support for those on low incomes, cliff edges can have the effect of disincentivising people from increasing their income via work if they cannot ensure that they’ll secure enough extra income to make up for the amount they'll lose as a result of no longer being eligible for social tariffs.

The challenge is to address these kinds of thorny issues, whilst keeping sight of the crucial longer-term vision: a comprehensive and coherent suite of social tariff schemes across essential markets, shielding those on low incomes from future price shocks and keeping them connected to what they need to keep living their lives.

At Citizens Advice, we’re up for this challenge - and we’re not alone. In partnership with abrdn Financial Fairness Trust, the Institute for Public Policy Research and Policy in Practice, we’re undertaking a new research project to build a blueprint for how the new government can best harness the potential impact of social tariffs to solve the cost-of-living equation for struggling households - in both the short and longer-term.

Citizens Advice will lead the project, drawing on our experience as statutory advocates for energy and post consumers as well as the unique frontline insights we have into the challenges people face - both with balancing household budgets and with accessing the support available.

The Institute for Public Policy Research will use innovative modelling techniques to build a picture of the scale of the affordability challenges facing low-income households across essential markets - as well as a multi-market cost-benefit analysis of different social tariff designs. Their work - which will make use of the IPPR tax-benefit model - will allow us to assess the various trade-offs inherent in scheme design, as well as the extent to which different funding options will be able to deliver the support needed.

Policy in Practice will focus on making social tariffs work for the consumers who need to use them, drawing on their experience developing practical tools to help drive take-up of social security. They will focus in particular on how the power of data sharing can be unlocked to drive automation in the delivery of social tariffs, as well as additional innovations that can simplify application processes for consumers where automation isn’t feasible (for example, single sign-up portals for multiple market schemes).

abrdn Financial Fairness Trust are generously funding this project, as well as leading some survey work examining public attitudes to the increasing cost of essentials, the role of social tariffs in shielding consumers on low incomes, and question of how far these schemes should be funded via consumer cross-subsidies.

The goal of this project is not to delay or impede shorter-term improvements to existing bill support schemes - indeed, the fact that such significant numbers of people are currently at risk of being priced out of essentials underscores the need to act without delay to unlock as much of the support currently on the table as possible. This project will push the government to take immediate, concrete steps to improve existing social tariffs, whilst at the same time charting a course for how to build on these shorter-term improvements towards a more comprehensive and effective suite of social tariff support in the longer run.

Endnotes

[1] Yonder Data Solutions surveyed 2,093 18+ GB adults between June 24th-25th 2024. All data unless otherwise stated is from this polling omnibus.

[2] Yonder Data Solutions surveyed 2,093 18+ GB adults between June 24th-25th 2024. All data unless otherwise stated is from this polling omnibus. 14.8% - just over 1 in 7 - of polling participants said they have stopped spending or cut it back to a level that has had a detrimental impact on their lives. This has been scaled up to GB population to equal 7,654,358 people. Great Britain population figure is based on ONS Census data from 2021. The total adult population for GB was calculated as 51.7 million based on this dataset extracted on 1 July 2024 . This was then used as a basis to extrapolate the Yonder polling.

[3] Calculation for unclaimed social tariffs based on: £1.68 billion going unclaimed in the broadband market according to estimates from Policy in Practice (April 2024). Nearly £300 million of total support scheme funding went unclaimed in 2022/23, according to data provided to Citizens Advice by the Consumer Council for Water.

[4] Citizens Advice, Negative Budgets data dashboard (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[5] Citizens Advice (2024) National Red Index: how to turn the tide on falling living standards

[6] Quotes taken from 32 in-depth qualitative interviews carried out by research agency Blue Marble. The interviews were conducted between 1st March and 2nd April 2024 with people who were struggling to afford at least one of broadband, motor insurance or water. The interviews were conducted, in-person online and over the phone. Quotas were used to ensure a good spread of participants by age, location, household income and gender, and to ensure disabled people, people with health conditions and those with different housing situations were represented. All participants for broadband and motor insurance were living in Great Britain. All participants for water were living in England.

[7] Yonder Data Solutions surveyed 2,093 18+ GB adults between June 24th-25th 2024. All data unless otherwise stated is from this polling omnibus. 10.1%, 5.8% and 4.6% had cancelled or cut back in water, broadband or car insurance respectively, and said they experienced some kind of impact beyond just moving to a cheaper tariff or using less water for non-essential purposes. These percentages were scaled up using the GB population figure based on ONS Census data from 2021.

[8] IPPR modelling used the IPPR Tax-Benefit Model with the Living Cost of Food Survey 2021/22 microdata to uprate household incomes to 2024/25, with costs uprated to 2024/25 using disaggregated inflation data from the Office for National Statistics. Essentials include modelled expenditure on water, energy, broadband and car insurance.

[9] Citizens Advice (2024) Fixing the foundations: The need for better targeted support for energy consumers

[10] Ofwat (2024) Press release: Ofwat sets out record £88 billion upgrade to deliver cleaner rivers and seas, and better services for customers. £94 average increase is for combined water and sewerage bills.

[11] IPPR analysis using IPPR Tax-Benefit Model with Living Cost and Food Survey - assumes water rates increase 21% between 2024/25 and 2029/30

[12] Citizens Advice (2023) Dialling up prices: Why mobile and broadband consumers need better protections from unfair pricing practices.

[13] Citizens Advice (2023) Press release: One million lose broadband access as cost-of-living crisis bites.

[14] Citizens Advice (2024) Popping the bonnet: Exploring affordability issues in car insurance and the ethnicity penalty.

[15] FairByDesign (2024) Press release: Low income drivers pay up to 48% more for car insurance. (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[16] Citizens Advice (2023) Press release: People of colour still paying £250 more on car insurance per year than white people.

[17] Association of British Insurers (2023) Increased cost of materials and labour continue to push up price of motor insurance in the last quarter. (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[18] Consumer Council for Water (2021) Independent review of water affordability.

[19] Citizens Advice (2024) Fixing the foundations: The need for better targeted support for energy consumers

[20] Citizens Advice (2024) The debt protection gap: Identifying good practice and policy solutions to improve support for consumers in debt.

[21] BBC (2023) Mobile and broadband price rises to be investigated. (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[22] Water UK (2023) Press release: Water companies propose largest ever investment. (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[23] Citizens Advice (2024) Shock proof: Breaking the cycle of winter energy crises.

[24] Consumer Council for Water (2023) Press release: Water bill rises will bring more uncertainty to struggling households, says CCW. (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[25] Example taken from Social Market Foundation (2023) Bare necessities: Towards an improved framework for social tariffs in the UK. Numbers updated to reflect this year's annual income and bill cap from Money Saving Expert.

[26] Unpublished information provided to Citizens Advice by the Consumer Council for Water (August 2024).

[27] Ofcom (2023) Press release: Half of low income households in the dark over broadband social tariff schemes. (retrieved 2nd September 2024)

[28] Ofcom (2023) Top trends from our latest telecoms pricing research.

[29] Policy in Practice (2024) Missing out 2024: £23 billion of support is going unclaimed each year.

[30] Ofcom (2024) Pricing trends for communications services in the UK.

[31]Citizens Advice (2024) Popping the bonnet: Exploring affordability issues in car insurance and the ethnicity penalty.

[32] Case studies taken from client stories from local Citizens Advice offices. All names and details have been changed to ensure anonymity.

[33] Policy in Practice (2024) Missing out 2024: £23 billion of support is going unclaimed each year.

[34] Citizens Advice (2024) Fixing the foundations: The need for better targeted support for energy consumers.