A better fit: How Universal Credit can improve income stability for employees with fluctuating and non-monthly pay

On this page

- Summary

- Policy options

- Introduction

- The UC monthly assessment is at odds with how people are paid

- The monthly assessment period’s knock-on effects

- Changing entitlement to Council Tax Support

- Making work hard, rather than making work pay

- The unintended impact of UC’s monthly model on financial security

- Policy options

The briefing is published in full below. Click here 1000 KB for a pdf version of the briefing, and here for an editable Google doc version.

Summary

Universal Credit (UC) is paid monthly in arrears. Entitlement is calculated through monthly ‘assessment periods’ (APs), which assess recipients' circumstances, based on the assumption that people have relatively stable monthly earnings.

The monthly AP model is at odds with how many people are paid. For those with variable earnings or who are paid non-monthly, UC’s design can be challenging: entitlement will drop when more than one pay packet falls in an AP, and UC payment dates can make income variations more extreme.

Many of the UC recipients Citizens Advice supports have no financial buffer, so friction between the monthly UC model and their earnings can lead to financial hardship. Interactions between earnings, the monthly AP, and other policies including the benefit cap, passported benefits, and Council Tax Support, can also mean the people we help lose out on other essential financial support.

The rigidity of UC’s model also makes working and receiving UC harder than it needs to be, including by making it difficult to anticipate how your income will change if you increase your earnings.

Policy options

Through the UC review, the government should consider how UC can be reformed to better reflect the reality of claimants' working lives. The review should explore:

Expanding Alternative Payment Arrangements (APAs), in line with Scottish choices, to give more people the option of being paid twice a month.

Accommodating greater flexibility by allowing claimants to change their AP and UC payment dates after their claim has started.

Ensuring passported benefits take multiple months of earnings into account, to avoid sudden cliff-edges in support when earnings fluctuate.

Improve communication with claimants about how earnings and UC entitlement interact.

Introduction

Many UC recipients need to manage income from employment and from UC, as well as the interactions between the two: 35% of people who claim UC are in employment, over 2.6 million people [1]. To calculate eligibility, claimants' circumstances are assessed through monthly assessment periods (APs), based on the assumption that they are paid monthly. The intention is that when income from employment increases, income from UC decreases.

UC’s rigid monthly approach was explicitly intended to “reflect the world of work”, but it is often at odds with the reality of recipients’ working lives [2]. In the UK, an estimated 1 in 7 employees have variable earnings (2.7 million people), and over 1 in 5 of the lowest paid workers are paid weekly [3]. The monthly AP is part of how UC “aims to encourage and support people to move into and stay in work” [4]. That UC is not based on a realistic understanding of low-paid employment, especially for those with fluctuating and non-monthly earnings, is a barrier to realising these aims.

Each year, Citizens Advice supports people for whom the monthly design of UC causes problems. One result of UC making monthly payments in arrears is the 5 weeks new claimants have to wait to receive their first UC payment. Both the 5 week wait, and the deductions resulting from the new claim advance loans many claimants have to take out to meet their essential needs during this wait, are significant sources of hardship [5]. However, even setting aside new claimants’ experiences and the impact of deductions, UC’s design creates ongoing challenges for working households whose wages don’t follow stable and/or monthly patterns.

In 2024/25, we advised over 31,100 people on the effect of their earnings on their UC payment amount. We helped over 2,100 people specifically with issues relating to fluctuating hours, and also over 2,100 with issues relating to non-monthly wages [6]. For those with variable incomes, the dates of their APs and when UC is paid can exacerbate, rather than reduce, the effects of fluctuations in pay. For those who do have stable earnings, but who are paid more frequently than monthly, UC income can drop suddenly when multiple pay packets fall within 1 AP.

Many of the people we support who receive UC are already struggling to meet their essential needs: over 50% of the people receiving UC we gave debt advice to last year were in a negative budget, where their income cannot cover their outgoings. For households like these, with little or no financial buffer, the sudden fluctuations in UC income caused by mismatches between earnings and UC’s monthly assessment model, can lead to hardship.

Falling above or below other income thresholds in the benefit system - whether that’s to qualify for additional, passported support, or to avoid being subject to the benefit cap - can mean more financial losses for the people we help. Even for those who can weather the costs of their changing UC income, the complexity of these processes can make it difficult to understand how pay and UC income interact, including how much better off you’ll be if you increase your hours.

Drawing on insights from our frontline advisers [7], this briefing sets out:

How the monthly assessment is based on a design of stable monthly pay with small variations (p.5)

How if claimants are paid non-monthly (p.7), or their income fluctuates (p.9) they experience exaggerated income fluctuations due to the way UC entitlement is assessed.

The knock-on effects of assessing income monthly on other benefit policies: passported benefits (p.11), Council Tax Support (p.12) and the benefit cap (p.13)

How the monthly AP can make working more challenging for the people coming to us for advice, including through interactions between fluctuating earnings and the work allowance (p.14)

How the combination of the monthly AP with UC income volatility contributes to making budgeting harder (p.15), and to financial shock, insecurity, and hardship for the people and families we support (p.16)

Policy options the UC review could explore (p.18)

The UC monthly assessment is at odds with how people are paid

UC claimants’ entitlement is continually assessed through a monthly assessment period, which starts from the day they first make their claim. For example, if someone applies for UC on the 13th of July, their first AP will run from the 13th of July to the 12th of August, and they will receive their first payment on the 19th of August - a week after the end of their first AP. This claimant’s AP will always start on the 13th of each month and end on the 12th of the following month.

The monthly AP allows UC to take into account changes in earned income, so that when income from employment increases in one month, income from UC decreases the following month. The monthly AP, and paying UC in arrears, is intended to make UC more responsive to changes in income (figure 1 and 2) [8].

Figure 1. Stable monthly earnings result in a stable monthly UC income

Figure 2. UC is designed to be responsive to small changes in earnings

Source: A worked example based on a fictional claimant, for illustrative purposes [9].

Friction between UC and non-monthly pay

For people who are paid weekly, fortnightly, or 4-weekly, an “extra” pay packet can fall into a monthly AP, impacting the subsequent UC payment. The amount of times claimants can be affected by having more paydays than usual in 1 AP varies depending on employment and pay frequencies. The DWP estimates that:

For those paid every 4 weeks, this can happen once a year,

For those paid fortnightly, this can happen twice a year,

And for those paid weekly, this can happen 4 times a year [10].

When an additional pay packet falls into the monthly AP, UC interprets this as an increase in earned income, and UC income is reduced as a result. The interaction between pay dates and UC can therefore make someone with a stable earned income experience a sudden drop in overall income.

For example, a claimant paid 4-weekly, is paid on 24th October and 4 weeks later on 21st November. A UC AP that runs from 23rd October to 22nd November will include 2 pay packets in 1 assessment, and double count their wages, when in fact their wages have not changed [11]. However, if this same claimant were paid every 2 weeks, (on 24th October, 7th November, and 21st November), the AP running from 23rd October to 22nd November would include 3, rather than the usual 2, pay packets. Later in the year, their AP covering 23rd April to 22nd May would again include an additional third pay packet.

As shown below (figure 3), the frequency and intensity of fluctuations in total household income (including UC plus wage income), depends on claimants’ pay frequency, because of how the UC AP counts pay packets. Those paid most frequently will see their total earnings vary most often, but by the smallest amount (because each wage packet is smaller, assuming claimants are paid the same rate), while those paid 4-weekly will experience 1 large income fluctuation per year.

Figure 3. Interactions between non-monthly wages and the monthly AP cause income fluctuations

Source: A worked example based on a fictional claimant, Simone (see also figure 1 and 2) [12].

Grace* and Matthew* recently got married and have 1 child. They work 20 hours and 12-15 hours per week respectively. They both get paid 4-weekly, which means sometimes their UC award gets reduced. For example, when they came to see our adviser, their award was about to drop from £900 to £100. When this happens, they struggle to pay the utility bills and for food. They had been referred to Citizens Advice by the Jobcentre, after their request for a budgeting advance was refused due to their income not meeting the threshold. Our adviser helped them to access a food bank.

*All names have been changed

Friction between UC and fluctuating earnings

Claimants experiencing fluctuating earnings also experience changing entitlement to UC. Fluctuating hours of paid employment can happen for various reasons, including employment structure (zero-hours contracts, part-time contracts, agency and temporary work), but also when someone needs to change their shifts - for example, if they are unwell, or need to look after a child who is unwell or whose childcare has fallen through.

In theory, by regularly assessing claimants’ circumstances, UC is designed to adapt to these changes in income - acting as a greater income top-up when income is lower, and a smaller top-up when income is higher, reducing the risk of over and underpayments (figure 2). However, because a claimant’s first AP starts the day they make a UC claim, the arbitrary claim date continues to determine AP and payment dates for the course of a claim, regardless of how well these dates fit the pattern of paydays and bills.

For the people we support, having misaligned UC and income payment dates means needing to manage 2 varying sources of income every month, creating serious budgeting challenges. Depending on the relative timings of APs and employment pay, UC can also exacerbate fluctuations in earned income, rather than dampen them.

Anna* is a single parent, who usually works 12-24 hours per week at National Living Wage. Anna has needed support from Citizens Advice twice because of fluctuations in her working hours. Once she came to her local Citizens Advice for support when she did not have any hours at work one week. Due to this drop in her income, she needed help from the Household Support Fund. 6 months later our advisers helped Anna again. This time, because she had worked more hours the previous month, her UC payment the following month would be £0. Fluctuating hours and UC payments have made it more difficult for Anna to meet her essential costs and to budget. She told our advisers she has no food, and is also struggling with rent arrears and council tax debts.

*All names have been changed

Being paid close to the end of an AP means there is only a small gap between receiving income from work and from UC - so UC is topping up that month’s wages. However, if someone is paid shortly after the end of their AP, there is an almost month-long delay between receiving the UC income tied to that month’s earnings, amplifying any changes in earned income.

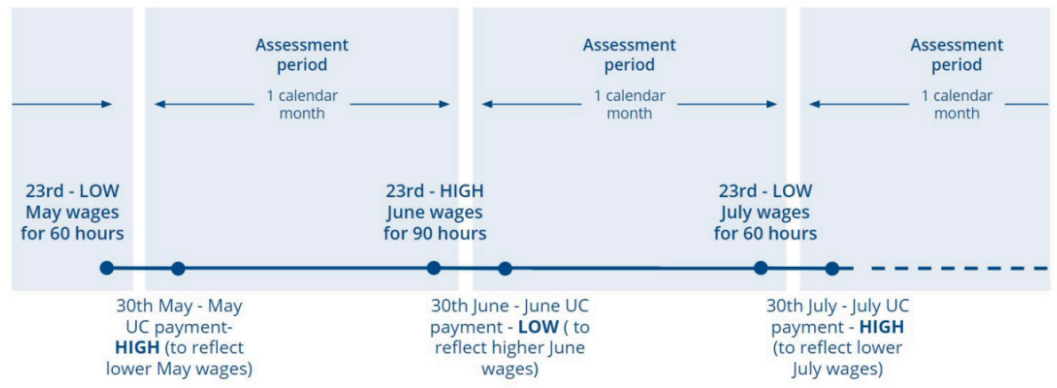

For example (figure 4 [13]), someone who receives their wages on the 23rd and their UC payment on the 30th will experience UC as topping up their wages, reducing fluctuation in overall income. In response to a month with lower wages (e.g. July in the figure below), they’ll receive a higher UC payment only 7 days later.

Figure 4: Alignment between paydays and UC APs means income fluctuations are reduced

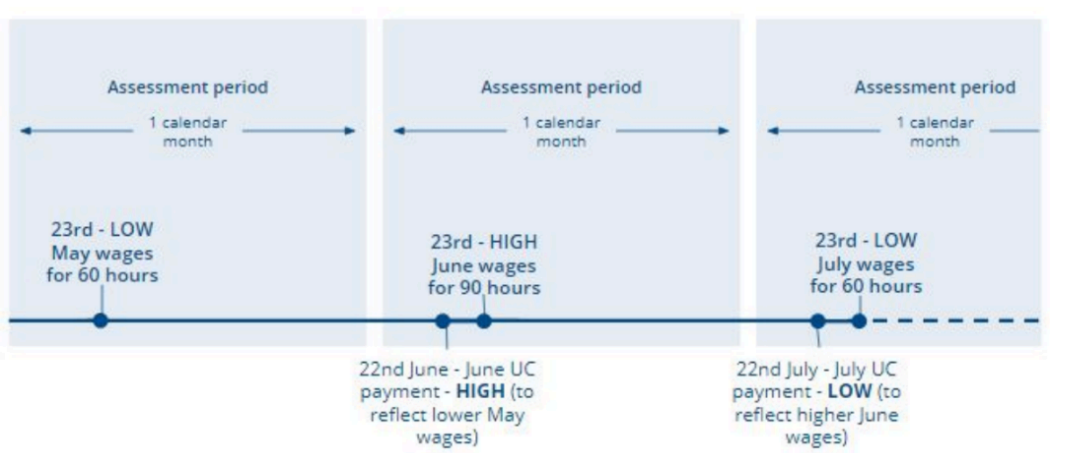

However, if the same claimant had started their UC claim on the 16th (figure 5), they would be paid UC on the 22nd of each month, with income assessed between the 16th - 15th of the next month. Instead of July’s UC payment topping up lower earnings from the same month, this claimant will experience a sudden drop in overall income as both earning and UC will fall at the same time.

Figure 5: Misalignment between paydays and UC APs means income fluctuations are amplified

The monthly assessment period’s knock-on effects

The monthly AP determines more than just the amount of a claimant’s routine UC payments. Receiving UC can act as a gateway benefit to other “passported” support, including Healthy Start cards, free NHS prescriptions and dental care, and Free School Meals (FSM). Where entitlement to passported benefits depends on earning below an income threshold, this income threshold is tied to the earnings assessed in a claimant’s AP. Claimants with changes in their monthly earned income can therefore lose access to important wider support if an income fluctuation brings them out of eligibility for passported benefits.

Similarly, an increase or drop in income can trigger other benefit policies linked to a monthly assessment of earnings. People with natural income fluctuations, or who have more pay packets than usual fall in an AP, can therefore lose out on other benefits. For example, their entitlement to locally-administered Council Tax Support (CTS) can change, or they can become affected by the benefit cap.

Losing access to passported benefits

To be eligible for Healthy Start cards, UC claimants need to earn less than £408 a month, per household. To be eligible for help with NHS costs, including prescriptions and dental care, UC households can only earn up to £435 a month, or £935 a month if they have a child, or have a health condition that limits their ability to work. As soon as a claimants’ earnings rise above these thresholds, they’ll lose their entitlement to these forms of passported support.

A similar problem affected whether those with variable earnings received the Cost of Living Payments, paid between July 2022 and February 2024. Claimants who received a UC nil award during the qualifying AP because of a change in their earnings (including a non-monthly pay pattern), missed out on hundreds of pounds of support - even if they were otherwise entitled to UC. While Cost of Living Payments are no longer an active policy, they are representative of how those entitled to additional support might lose out in the future if eligibility for emergency benefit payments is linked to earnings in a single monthly AP.

Josephine* is a single parent who works 20 hours per week. She was awarded £0 UC when she received an extra pay packet in her monthly AP, which happens once a year because she is paid every 4 weeks. Receiving £0 UC that month meant Josephine wasn’t eligible for the Cost of Living Payment. Josephine had received other Cost of Living Payments before, and would have received this one if the qualifying AP hadn’t been the one period a year when she received 2 pay packets in an AP. Josephine was relying on receiving the Cost of Living Payment to help tackle her rent arrears.

*All names have been changed

Until eligibility for FSM was expanded to all households in receipt of UC in June 2025, eligibility was also tied to an earnings threshold. However, in contrast to other passported benefits, FSM eligibility took into consideration earnings from up to 3 consecutive APs. As a result, one-off fluctuations in income would not mean losing FSM entitlement [14].

Changing entitlement to Council Tax Support

Fluctuations in assessed income can also have knock-on effects on entitlement to support outside the UC system, primarily locally-administered Council Tax Support (CTS). How CTS is designed varies by local authority, though what support claimants can access usually depends on an assessment of earnings.

CTS interacts with earnings either through a tapering system, where entitlement gradually reduces as earnings increase, or through an income-band model, where support only changes when earnings move into a different band. Under tapering schemes, local authorities need to recalculate CTS entitlement each month a claimant’s income changes (whether because of volatile pay, or non-monthly wage patterns being interpreted by UC as fluctuations in earnings). This causes stress and confusion for the people we support. Under income-banded schemes, although CTS entitlement is likely to vary less frequently, even small fluctuations in earnings can change someone’s CTS income band - leading to significant and sudden cliff edges in CTS support.

Georgia* is paid weekly and also receives UC. She visited her local Citizens Advice for help with her CTS. Georgia had received multiple letters from her council telling her every time her entitlement to CTS had changed. This causes Georgia stress and makes it very challenging for her to understand her finances. Our adviser helped Georgia understand that having her weekly pay assessed monthly by UC is having a knock-on effect on her CTS, which goes up and down depending on whether she has 4 or 5 wage payments in a month.

*All names have been changed

Becoming affected by the benefit cap

The benefit cap is the maximum amount of money the DWP will pay in benefits, depending on household make up and location. Claimants are not affected by the benefit cap if they, or someone they care for, is disabled - or if they earn £846 or more per month. A household who would otherwise be affected by the benefit cap may not have their UC entitlement capped for an initial 9 month ‘grace period’. However, one of the conditions of being eligible for the grace period is having earnings over £846 per month for each of the past 12 months.

Both the ongoing impact of the benefit cap, and entitlement to the grace period, therefore depend on consistently earning above the £846 monthly threshold. People who’ve earned above £846 a month, on average, over the course of a year, but who have variable earnings which drop below the threshold, will have their UC capped, losing out on essential support they’ve been assessed as needing.

Sean* has 3 children, works part-time, and is paid weekly. In the months where Sean receives 4 pay packets in an AP, his UC is affected by the benefit cap because he has earned below the £793 requirement [15]. When he receives 5 pay packets, his earnings will be above £793, so his UC will not be capped, and will be £105 higher. As a result of the benefit cap, Sean is much worse off when 4 pay packets fall in an AP instead of 5, even though his weekly earnings haven’t changed.

*All names have been changed

Making work hard, rather than making work pay

Weaker work incentives via the the work allowance

For many UC claimants, as soon as they start earning money from employment, their UC starts to be tapered away. The taper rate is currently 55%: for every £1 a claimant earns from employment, UC payment goes down by 55p.

However, claimants with children, or with a disability or health condition that affects their ability to work are entitled to a “work allowance”, allowing them to earn a certain amount before their UC starts to be affected by the taper.

For people receiving UC who have a work allowance, a fluctuating income (whether from a change in hours or a non-monthly pay pattern) can mean more of their UC will be affected by the taper, reducing their overall income. For example, a parent who receives support with housing costs through UC can earn £411 a month before their UC income starts to be tapered away as their earnings rise. If this person earns £820 over a 2 month period, it matters whether this is from 2 equal earnings of £410 a month, or if their earnings fluctuate above the work allowance.

Earning £410 each month is within the work allowance, and means they are able to keep all their earnings from employment and their full UC entitlement. However, someone with a fluctuating income who has earned £610 in the first month, and £210 in the second, would be almost £110 worse off over this 2 month period, even though they’ve earned the same amount as someone with a consistent monthly income.

| Stable income - Month 1 | Stable income - Month 2 | Fluctuating income - Month 1 | Fluctuating income - Month 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total UC entitlement [16] |

Stable income - Month 1

£1251.04 |

Stable income - Month 2

£1251.04 |

Fluctuating income - Month 1

£1251.04 |

Fluctuating income - Month 2

£1251.04 |

|

Monthly gross earnings |

Stable income - Month 1

£410 |

Stable income - Month 2

£410 |

Fluctuating income - Month 1

£610 |

Fluctuating income - Month 2

£210 |

|

Tapered UC |

Stable income - Month 1

£0 |

Stable income - Month 2

£0 |

Fluctuating income - Month 1

- £109.45 |

Fluctuating income - Month 2

£0 |

|

UC after taper |

Stable income - Month 1

£1251.04 |

Stable income - Month 2

£1251.04 |

Fluctuating income - Month 1

£1141.59 |

Fluctuating income - Month 2

£1251.04 |

|

Total income |

Stable income - Month 1

£1661.04 |

Stable income - Month 2

£1661.04 |

Fluctuating income - Month 1

£1751.59 |

Fluctuating income - Month 2

£1461.04 |

|

2 month total |

Stable income - Month 1 |

Stable income - Month 2

£3322.08 |

Fluctuating income - Month 1 |

Fluctuating income - Month 2

£3212.63 |

Managing changing wages and changing UC

People seek our advice on fluctuating hours and non-monthly pay because they need help when their UC payment changes. Our advisers tell us that the people they support do not always understand why their UC has changed, and experience the drop in UC as a sudden and unanticipated change in their benefit income. The shift in UC can make budgeting much harder for the people coming to us for help, and trying to resolve the issues of UC fluctuation can be stressful.

Beverly* received no UC payment this month due to being paid twice in her last AP, because she is paid 4-weekly. She was unaware of this issue because she has recently had to move from Tax Credits as part of the managed migration process. Beverly received Tax Credits for around 10 years, and had a strong understanding of her income. She has been very confused by how her UC interacts with her earnings, which has left her feeling very anxious and stressed. Without the money she expected to receive through UC this month, she doesn’t know how she’ll pay her mortgage. Beverly now needs to learn how to re-manage her finances with the anticipation of a sudden drop in UC happening once a year when she receives 2 pay packets in 1 AP.

*All names have be changed

Even if the people we help are aware of how their UC might vary, the reality is that many do not have the means to weather these income fluctuations. The current UC system makes working harder than it needs to be for those with non-monthly payments. Instead of managing income fluctuations our clients could be focusing on employment.

The unintended impact of UC’s monthly model on financial security

Although it was not the intention of UC design to shift those with a stable low employment income into experiencing household income volatility, in practice this can be the effect on some of the people coming to us for support.

Working households experience financial hardship

The interaction between pay frequencies and income fluctuation with UC’s monthly assessment causes distress and financial hardship for the people who come to us for support. In 2024/25 16% of the people we advised on income fluctuation (hours and non-monthly payments), also needed advice on food banks. UC claimants do not always have the financial safety nets needed to manage fluctuations in income.

Our clients have told advisers that because of the knock on effect of being paid non-monthly, UC can drop when other expenses occur, making it more challenging to afford regular bills like rent and energy.

Jade* received 2 wage payments in 1 UC AP, leading to a reduction of UC the following month. Her financial difficulties are compounded by her last wages being reduced when she took time off work because her daughter was sick. Because Jade works in a school, her next month's wages will again be reduced when she has fewer hours over the school holidays. Jade says she is usually fine with money, but is being forced to use a foodbank this month. She only has £30 left until the end of the month, after paying for rent and essentials. She has no money to buy a school uniform for her daughter.

*All names have been changed

Like for Jade, the hardship caused by misalignment between UC and wages can have consequences for parents’ being able to meet their children’s essential needs; nearly half of the people we advised on fluctuating hours and non-monthly payments have dependent children in their household.

Policy options

An idealised model of stable, monthly employment is the foundation of UC’s current design. For the people we support who have fluctuating and non-monthly earnings, this model is limiting UC’s effectiveness, leading to stress and financial hardship. The UC review is an opportunity to base UC on a more realistic understanding of the practicalities of low-paid employment. To mitigate how UC can increase and mirror the income volatility experienced by low-paid employees, the UC review should consider options for better supporting working households:

1. Expanding Alternative Payment Arrangements (APAs), in line with Scottish choices

Through Universal Credit Scottish Choices, claimants in Scotland can choose to receive their UC payment twice a month, rather than monthly. By contrast, in England and Wales, more frequent payments are restricted to cases where there is ‘risk of financial harm to the claimant or their family’. Evidence from Citizens Advice Scotland suggests that the choice to receive UC twice a month can support claimants’ budgeting, particularly for those who are paid weekly [17]. Expanding Alternative Payment Arrangements to all claimants, in line with the options already available in Scotland, could smooth the income fluctuations exacerbated by UC’s monthly model.

2. Allowing claimants to change their AP and UC payment dates after their claim has started

Basing ongoing AP and payment dates on an arbitrary initial claim date can exacerbate overall income fluctuations. Allowing claimants to shift to a new set of AP and UC payment dates, which align with when they receive their wages, could enable UC to more effectively top up low wages and soften the impact of variable earnings.

3. Ensuring passported benefits, and other policies linked to earnings, take an average of multiple APs into account.

To avoid sudden cliff-edges in support when earnings fluctuate, passported benefits and UC policies linked to earnings should take earnings from multiple APs into account. The approach of looking at average earnings across 3 APs, as was used to determine FSM eligibility when this support was still linked to earnings, could be applied to Healthy Start and NHS costs support.

The benefit cap overrides entitlements to arbitrarily reduce the income households can receive from the benefits system, particularly affecting households with children. To tackle child poverty, the benefit cap needs to be abolished. Short of this, basing the benefit cap and grace period on a period of average earnings, rather than individual APs, could soften the cap’s impact for households with fluctuating and non-monthly earnings.

4. Improve communication with claimants about how fluctuations in earnings will impact on benefit income

Greater transparency and communication about how much UC will pay out would help remove some of the mystery surrounding payments. The budgets of the people we support are already stretched, and variation in UC can be a shock to those with low incomes, in particular when it impacts entitlement to other benefits. Improving communication about how changes in wages can impact on future UC payments (supporting clients to know what pay to expect) could enable claimants to engage with employment, while receiving UC, with more confidence. UC needs to empower the people we support to progress in employment, not cause confusion.

Acknowledgements

This briefing was written by Sarah Hadfield and Julia Ruddick-Trentmann. The authors are grateful to Craig Berry, Simon Collerton, Rachel Ingleby, Jagna Olejniczak, Maddy Rose, and Erica Young for advice and support with this briefing.

Notes

Department for Work and Pensions (February 2025), Statxplore: People on Universal Credit.

Explanatory Memorandum to Universal Credit Regulations 2013, 7.29. Available here.

According to analysis by the Resolution Foundation, in the UK between 2014/15 and 2018/19, 21% of workers in the lowest hourly pay quintile were paid weekly. Mike Brewer, Nye Cominetti, and Stephen P. Jenkins, (2025), Unstable Pay: New estimates of earnings volatility in the UK, Resolution Foundation.

Explanatory Memorandum to Universal Credit Regulations 2013, 7.23. Available here.

In 2024/25, we helped over 9,000 people with issues related to repaying new claim advance loan deductions, over 2 in 3 of whom also needed advice on accessing food banks.

11% of the people we advised on non-monthly pay needed advice on fortnightly wages, and 46% and 47% needed advice on 4-weekly and weekly wage payments respectively.

Sources include data from our case management system, and written evidence submitted by advisers which highlights the problems the people we support face when interacting with the benefits system. This briefing considers evidence submitted between 1st January 2024 and 30th April 2025.

Tax Credits, by contrast, calculated entitlement based on total income from the previous tax year. This led to a higher risk of over and underpayments if income changed over the course of the year, or was significantly different from the previous year

Figures 1 and 2 model the circumstances of a fictional claimant, Simone, who works 32 hours per week, at the National Living Wage (NLW), and is paid monthly. She lives in a private rented 2 bedroom flat with her 3 year old child, receiving £155.34 per week in UC housing costs support (the maximum Local Housing Allowance rate). In figure 1, we assume Simone works 32 hours per week all year. In figure 2, we assume she usually works 32 hours per week, but that she has taken on 2 additional 8 hour shifts at NLW in month 4, and 2 fewer 8 hour shifts at NLW in month 8. Calculations for figures 1, 2, and 3 do not include any support received for childcare costs, and assume that benefits rates do not change over the 12 months shown.

Department for Work and Pensions (2025) Universal Credit and earnings.

The UC regulations were changed in 2020, following a legal case concerning the negative impact on claimants who are paid monthly, but where an additional wage payment has fallen into 1 AP (e.g. due to pay dates shifting because of weekends or bank holidays). The Universal Credit (Earned Income) Amendment Regulations 2020 allows an extra pay packet to be treated as if it had fallen in a different AP. This same option of shifting pay to another AP is not available to claimants with 4-weekly pay frequencies, see Child Poverty Action Group (2021), Universal credit, earned income and monthly pay.

We have modelled how receiving her wages at different frequencies would make Simone’s income from work and UC vary, even if all her other circumstances (including hours worked per week and hourly wage) stay the same.

Example and figures 4 and 5 originally published in Citizens Advice (2018) Universal Credit and Modern Employment: Non-traditional Work.

In addition, a child would only lose access to FSMs at the end of their current phase of education. Department for Education (2025) Free school meals: Guidance for local authorities, maintained schools, academies and free schools.

The earning threshold was £793 until 31 March 2025. GOV.UK: When the benefit cap affects your Universal Credit payments.

Entitlement calculated using 2025/26 benefit rates, assuming the claimant is single and over 25, has a child born before 2017, and receives a UC Housing Element of £511.90 per month (based on the mean rent for a new social housing letting, for a 2 bedroom flat in England. See Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2025) Social housing lettings in England, April 2023 to March 2024).

Citizens Advice Scotland (2022) Briefing on Scottish Choices for Universal Credit claimants, unpublished, and Citizens Advice Scotland (2020) written evidence submitted to the Scottish Affairs Committee: Welfare in Scotland Inquiry.