The youth penalty: lower pay, lower benefits, higher sanctions

Recent Universal Credit changes will disproportionately affect young people

One of Universal Credit’s (UC’s) lesser known features is the Administrative Earnings Threshold (AET). While it might sound obscure, the AET determines the extent of conditions that someone on UC might have attached to their benefits. And more conditions means a higher likelihood of sanctions, like losing income if the conditions are not met.

In short, people getting UC need to be earning more than the AET to escape conditions around searching for work, or higher pay, that jobcentres attach to UC awards.

This is why a series of government decisions to raise the AET needs more attention, especially given that young people are likely to be most negatively affected.

AET increases are accelerating — widening the scope of conditionality and sanctions

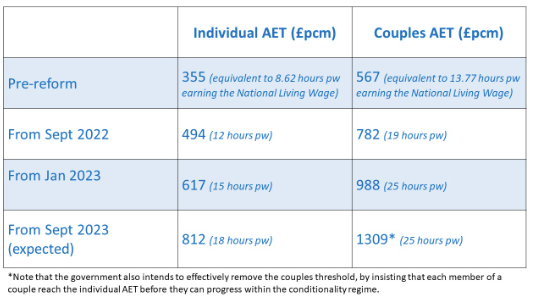

Our report on in-work conditionality highlighted recent increases in the AET, and the government intends to go even further.

With a higher AET, more people on UC will earn less than the new threshold, unless they can quickly increase their hours or pay. In most cases, they’ll become subject to an intensive work search (IWS) regime, meaning stricter expectations of searching for higher paid work will be applied. Previously, they’d have fallen into the ‘light touch’ regime.

IWS means more strings are attached to UC awards, which may mean more people receive sanctions (withdrawal of or reductions in their benefits for a period of time) for things like if they fail to show they’ve been searching for higher-paid work, or miss a jobcentre appointment.

Young people will bear the brunt of these changes

We know from government data that young people on UC are already more likely to be subject to conditionality. And among those on UC subject to conditionality, young people are more likely to receive a sanction — particularly people in their early twenties (this is partly because they’re less likely to have a disability or long-term health condition, and so are more likely to be subject to the maximum job search requirements).

The AET changes are likely to make this situation worse. Equality impact assessments produced alongside the AET decisions show that young people are far more likely than other age groups to have earnings below the new threshold, and so are more likely to be subject to stricter conditionality.

Young people are facing a triple whammy

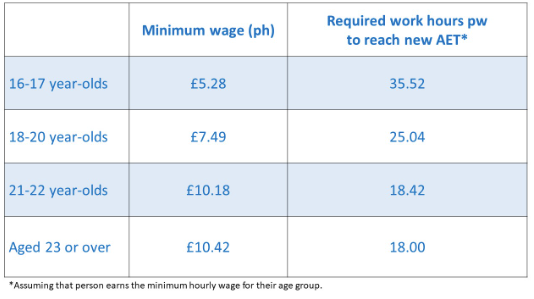

The explanation for this impact is relatively simple: most young people don’t qualify for the National Living Wage (NLW), even though it’s the reference point for calculating the AET. The NLW rate of £10.42 per hour is only available to those aged 23 or over. People aged 17 or below, 18–20 and 21–22 are eligible instead for National Minimum Wage (NMW) rates of, respectively, £5.28, £7.49 and £10.18 per hour.

This means low-income young people have to work more than older groups to rise above the AET, even more now as the threshold increases.

A 20 year-old on the NMW, for example, would have to work more than 25 hours per week, and a 17 year-old more than 35 hours per week, in order to reach the new threshold (in contrast to 18 hours for people aged 23 or over).

This is on top of the fact that people aged 24 or under already get lower rates of UC — a standard allowance of £291.11 per month for single recipients, compared to £368.74 per month for those 25+. Single people aged under 35 without children also receive lower amounts of additional support for housing costs.

As it stands Gen Z face a lower minimum wage, lower benefits, and tougher conditionality requirements than older workers receiving UC. We may all dream of being 20 again, but seeing the state of welfare today for the youngest workers, I think most of us might think twice.